| If you do

NOT see the Table of Contents frame to the left of this page, then

Click here to open 'USArmyGermany' frameset |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Berlin

Brigade |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Headquarter & Miscellaneous | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Berlin Brigade Commanders Headquarters, Berlin Brigade Berlin Brigade Organization Charts Berlin Crisis Units not attached to Berlin Brigade (Lodger) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Berlin Brigade History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Berlin "patch" is the same as that worn by US Army, Europe except that it is surmounted by the Berlin arc. It is derived from the insignia designed by General Dwight D. Eisenhower's command during World War II, Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF). The original SHAEF patch was on a field of black ("heraldic sable"), symbolizing Nazi oppression. In July 1945, the field was changed to blue ("azure") symbolizing a state of peace, the restoration of which was the objective of the World War II allies. Upon the field of blue is shown the sword of liberation in the form of a Crusader's sword, the flames arising from the hilt and leaping up the blade. This represents avenging justice by which the enemy power was broken in Nazi-dominated Europe. Above the sword is a rainbow, emblematic of all the colors of which the National Flags of the Allies are composed. The distinguishing Berlin arc has been worn by the US Army in Berlin since 1951. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1945 - 1980 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: "The Story of Berlin Brigade", Pamphlet 870-2, US Command, Berlin and US Army, Berlin, 1981.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

USCOB/USAB

Pam 870-2

The Story of Berlin Brigade |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Military

History Branch, G-3 Division

Headquarters US Command, Berlin and US Army, Berlin |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1981

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. FORMATION

AND LINEAGE

The Berlin Brigade was formed at the height of the Berlin Wall crisis. It was created from units already in Berlin by General Orders from the Commander-in-Chief, United States Army, Europe. General Bruce Clarke ordered that from 1 December 1961 the core of the United States military presence in Berlin, the living symbol of America's protection for the people of free Berlin, would be known as the United States Army Berlin Brigade. Between 4 July 1945 and 1 December 1961 the security force in Berlin had been known by several different names. During the first eight months of the occupation three famous American divisions in succession occupied the former capital of the German nation: The 2d Armored Division, the 82d Airborne Division and the 78th "Lightning" Infantry Division. From 1946 through the era of the Berlin Blockade and Airlift the troop command was known as Berlin Military Post. During the ensuing decade it was known variously as Berlin Command and the U.S. Army Garrison, Berlin. During the past 18 years, however, the name "Berlin Brigade" has stuck.* It symbolizes the pride and traditions of some 100,000 men and women of the United States Army who have served their country east of the river Elbe, the defenders of freedom. More than two years before the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was formed, the United States had defied the Russian blockade and, together with Great Britain and France, had pledged itself to uphold the freedom and security of West Berlin. During the thirty-three years since 1946 when the first permanent garrison was formed, the Berlin Brigade has never fired a shot in anger. That is a measure of its success. Probably no force of its size in history has contributed more to peace and freedom in the world. Every man and woman privileged to serve with the American forces in Berlin should know how we got here and why we stayed here. This is the story of the Berlin Brigade. *Since there has been little change in the missions of the U.S. garrison in Berlin since the early 1950's, it will be referred to throughout as the Berlin Brigade. 2. FIRST SIGHT It was the beginning of July in 1945. A great world city - Berlin - lay prostrate and largely devastated. From the air it looked like a desolate stone desert, with its roofless buildings, its heaps of rubble. Two years of intense bombing and a fanatical struggle between the last-ditch defenders and the attacking Soviet Army had left the city in ruins. For two months, from the cessation of actual fighting (2 May 1945), the city had been looted in the name of reparations. Refrigeration plants, mills, whole factories, generator equipment, lathes and precision tools were dismantled and loaded in rail cars for shipment to the Soviet Union. Inhabitants of the defeated capital, dazed, were just beginning to attempt to provide themselves with the bare necessities of life. Dully they sought food, items of clothing, anything to put them back in the battle for human survival. It was in this simmering cauldron of a city -- a setting as historic as the great sacks of Rome -- that the Berlin Brigade was born. The Berlin Command had a modest enough beginning on the first day of July, 1945. Colonel Frank Howley led a contingent of military government personnel into the city. The Russians, who up to then had full control of the city, had not allowed the Americans to scout their sector before entering. As a result, hundreds of officers and men had to find places to stay in the ruins. Many wound up sleeping in tents in the Grunewald. By the Fourth of July, Major General Floyd L. Parks, the first American Commandant, together with elements of the 2d Armored Division had moved in to occupy the American Sector in the southwest areas of the city. Ceremonies in several parts of the U.S. Sector marked the takeover. At the Telefunken electronics factory -- now McNair Barracks -- Sherman tanks of the "Hell on Wheels" Division lined up opposite two companies of the Soviet Army. General Omar Bradley flew into Berlin especially to represent the United States on this historic occasion. In fact, U.S. forces did not complete the takeover in the American Sector until 12 July. Finally, most of the Russians moved out, but not without considerable "urging". * The home of the 2d, 3d, and 4th Battalions of the 6th U.S. Infantry. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. GETTING ORGANIZED Meanwhile Lieutenant General Lucius Clay and Robert Murphy, respectively Deputy Military Governor and Political Advisor to General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, had flown to Berlin for the initial conferences with the Russians. This was the first gathering of the Allied Military Governors for Germany who together made up the Allied Control Council. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| for the four

victorious Allies of World War II. There was no central government

for conquered Germany. The four military governors, acting by unanimous

decision in the Allied Control Council, exercised supreme governing

authority in the four Zones of Occupation. Symbolically, the Council

established itself in the mammoth building in Berlin's Schoeneberg

district which had housed Imperial and Nazi Germany's supreme court.*

There followed countless committee meetings and conferences of the

military governors. The object was to fulfill the terms of the Potsdam

Agreement to provide one central, military government for all four

Zones of Occupation. The Council was unable to realize that objective.

Communist obstructionism was obvious from the beginning. By the fall

of 1946 Secretary of State James F. Byrnes publicly declared: "The

Allied Control Council is neither governing Germany nor allowing Germany

to govern itself." * Still located there is the four-power Berlin Air Safety Center or BASC. 4. MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND THE MISSION During 1945, however, the spirit of cooperation that had led the Allies to victory in World War II was not completely lost. But minor irritants were evident even then. Practically every effort of the Allied Kommandatura to restore order and a semblance of normalcy to Berlin was to some extent thwarted by the Soviets and their German sympathizers. The fact that the Red Army had taken Berlin and had been its sole occupiers for two months before the Western Allies moved into their Sectors gave the Russians an advantage that they were not slow to exploit. In the wake of the Russian Army, German Communists who had fled to the Soviet Union during the Hitler era returned to Berlin. Typical of this group was Paul Markgraf, whom the Soviets promptly named as Police President of Berlin. Since only persons who could prove that they had not been Nazis were eligible for government posts under the occupation, the Soviets were able to fill key posts in all four Sectors with pro-Soviet functionaries. In addition, the Soviets took advantage of the initial era of good feeling to influence the organization of the Allied Kommandatura. As a result it was easy for them to block real four-power government for the whole city, since they had insisted that all decisions of the Kommandatura must be unanimous. A Soviet veto was enough to disrupt or block constructive action. The Kommandatura itself, the sole legal authority in Berlin, had to transact business in four languages -- English, French, Russian and, of course, German. The end of the War in the Pacific added to the problems of American participation in the four-power occupation. Redeployment and demobilization of U.S. forces began almost immediately. Some military units in Berlin reportedly experienced a personnel turnover of as much as 300 percent in a single month. To cope with the problem of maintaining order it was necessary to re-train battle-hardened soldiers in the techniques of civil police duties. Early in 1946 they were assigned to a mobile organization, a provisional constabulary squadron. This lightly armed unit patrolled the city in cavalry scout cars. One of its principal duties was to curb the black market gangs and the smugglers who trafficked in all types of contraband. Such gangs were, in part, responsible for further inflating the ruined Germany currency and the spreading economic chaos. The first permanent units of the Brigade, the 16th Constabulary Squadron and the 759th Military Police Battalion were formed and had taken over these missions by 1 May 1946. New operational techniques had to be devised for using soldiers to control a civilian population governed jointly by four different countries. Differences in language magnified differences in temperament, legal philosophy and national outlook. Cooperation with Berlin's rehabilitated civil police, controlled by a Moscow-trained police president, was difficult. In many instances, problems were generated by a combination of honest misunderstanding and Soviet opposition. Eventually, however, procedures were developed to facilitate routine operations among the four occupation powers and the Berlin police. The occupation was not a complete failure. The breakdown of the four-power occupation machinery was gradual. When it finally occurred, in 1948, it was, like most milestones in Berlin's post-war history, the result of a calculated Soviet policy offensive. In this complex and sensitive situation, the Army stood ready to guarantee United States rights under international agreements. It contributed significantly to the success of State Department programs to provide the basic human necessities for the German people and to restore economic order. During 1946-47 it became increasingly clear that the Soviet Union's one-sided interpretation of the Potsdam Agreement violated the spirit of the agreement, as well as the United States' concept of fundamental human rights. With the Soviets demanding reparations in excess of what Germany could produce and blocking efforts in the Control Council to implement economic reforms, the Western Allies found themselves, reluctantly at first, taking the first steps on the road to reconciliation and alliance with their former enemy. 5. PROBLEMS AND MISSIONS During the winter of 1945-46 U.S. forces were faced with the practical problems of keeping two million Berliners in the Western Sectors alive in a shattered city. Under the U.S. Military Government, the Brigade went to work. Results were quickly apparent. Restoration of basic services was the first requirement and the re-lighting of only 1,000 gas-fueled street lamps throughout Berlin, on 2 March 1946, was an event of sufficient importance to convince untold numbers of the city's inhabitants that perhaps there was some light for the future, too. The spirit of the Berlin Brigade was perhaps lighted by that first, symbolic step back on the road to self-sufficiency and self-esteem for the Berliners. However small, it offered hope for a new beginning. The problems of rotation and demobilization plagued the Brigade during 1946. Rotation without replacement had so decimated the 78th Infantry Division that by November 1946 it was reorganized and designated the 3d Battalion of the 16th Infantry and became part of the garrison. The composition of the Berlin security force proved adequate to the tasks it was called upon to perform during 1946-47. The concept of the force and its missions changed during 1948-49, however, when the level of international tensions was first characterized as a "cold war." By the spring of 1950 Berlin Brigade's primary missions had been defined approximately as at present: to deter aggression, counter wide-spread civil disturbance and defend the city. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. BLOCKADE AND AIRLIFT By the end of 1947 Soviet obstruction had brought attempts at four-power government in Germany and Berlin to a standstill. Attempts to establish democratic institutions and a degree of self-government were also impeded by the Soviet-controlled Socialist Unity Party or SED, which later became the ruling Communist party in East Germany. The breaking point came in March 1948 when the Soviet Military Governor, Marshal Sokolowsky, walked out of the Allied Control Council. This shattered the remnant of four-power government for all Germany. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The

Allies, led by the United States, responded with an unprecendented

use of air power. When the first supply planes landed in Berlin on

26 June 1948, no one knew how long it would last or if it would work.

But the Soviets were clearly violating international agreements. General

Clay told President Truman that the Berliners would prefer unknown

hardships to Communist rule and that they had the will to stick it

out. The Berlin Airlift was on. The Allies, the Berliners, the Air Force and the Army all share in the credit for the success of the airlift. To supply a city of over two million people with the planes available required a miracle of organization on the ground. "Turn-around time" became one of the vital keys to the success of the Airlift. Berlin Brigade personnel devised off-loading systems, worked as guards and checkers and supervised a German workforce of thousands. Army engineers constructed a new runway at Tempelhof in 49 days. On the site of a former German training area, they constructed a new airfield -- Tegel. Three months after construction started, airlift planes were landing at Tegel. During this "cold war" battle for Berlin field training and many other normal garrison activities were curtailed. Tactical and service units, the available manpower of the Allied garrisons in Berlin was wholly committed to the support of the vital lifeline, the Airlift. The Blockade lasted for some 324 days. By agreement between the Ambassadors of the four powers in the United Nations -- the so-called Jessup-Malik agreement -- the Blockade was formally ended on 12 May 1949. Operation VITTLES, as the airlift came to be called, continued for another two months while the surface transportation system was restored and stocks in the city brought up to normal levels. The world breathed a sigh of relief when the Blockade was ended peacefully. Berlin had weathered its first major post-war crisis. Out of those eleven months of tension and exertion in a common cause, the foundation of a new bond of sympathy and mutual respect between the German and American people was laid. 7. NEW ERA - THE BRIGADE IN TRANSITION May 12, 1949 was more than the end of the Berlin Blockade. The same day the Allied Military Governors approved a draft constitution for the Western Zones of Occupation, the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany. It was the beginning of a new era. The end of the Blockade was followed by a period of reorganization. The military government in West Germany ended and in its place the Allied High Commission, eventually located with the new Federal German Government in Bonn, was established to supervise West Germany's transition to full sovereignty. In Berlin the remaining military government functions were combined with those of the U.S. Commandant in a new post, that of the U.S. Commander, Berlin (USCOB). At the same time Berlin Brigade was relieved of its assignment to the Office of Military Government and was assigned directly to the United States Army, Europe. This assignment remained unchanged until December 1961, when USCOB became part of the Brigade's Army chain of command as the Commander, U.S. Army, Berlin. In 1950 Berlin Brigade began to acquire some of its now familiar characteristics. Most notable was the beginning of the long association between the Brigade and the 6th Infantry. As a result of widespread riots in the city, occasioned by a Communist-sponsored "All German Youth Rally," the 6th Infantry was activated and assigned to Berlin. Throughout all ensuing organizational changes, the 6th Infantry has formed the core of Berlin Brigade's combat strength. The last of these changes occurred in September 1972. Since that time the Brigade's three infantry battalions have all borne the flag of the 6th Infantry. 8. BETWEEN CRISES Throughout the 1950's and 60's Berlin remained a crisis center. Then as now the daily activities of the Berlin Brigade were closely linked to larger policy issues. From the beginning the United States took the position that the right to be in Berlin -- under wartime and post-war agreements which the Soviet Union had not successfully repudiated -- was inseparable from the right to get to Berlin, the right of access. This became especially important on the autobahn, where, unlike the rail lines and the air corridors, no formal post-war agreements with the Soviets confirmed access rights. On the autobahn the men of the Berlin Brigade, in single vehicles and convoys, were frequently subjected to Soviet and East German harassment. The object was to force upon the Allies new and ever more complex restrictions on the exercise of their access rights. The only way to maintain Allied rights and to assure that the Soviets did not erode them was to use them steadily and oppose all efforts by the Soviets to introduce changes to which the Allies had not agreed. Exercising Allied rights on the surface access routes became one of the Brigade's most important missions. As a result, Brigade soldiers were often the first to bear the brunt of new Soviet tactics and policies. 9. INTENSIFYING CRISIS November 1958 marked the beginning of a new and more prolonged period of crisis in Berlin and on the access routes. In what was known as the "Krushchev Ultimatum," the Soviet Union posed a serious threat to the future status of the city. The United States rejected the ultimatum and its six-month deadline passed without incident. A conference of Western and Soviet foreign ministers, which convened the following summer (June 1959) in Geneva, failed to reconcile the longstanding differences. The Allies demanded free, U.N.-supervised elections in all Germany as a preliminary to reunification. At this 1959 meeting of the four foreign ministers, the first since the Berlin Conferences of 1954, the Soviets made what they knew to be unacceptable demands. In effect they said that, in the foreseeable future, there was no possibility of agreement to reunify Germany on terms acceptable to the United States and the Western Alliance. With hopes of reunification wining and international tensions over Berlin running high, East Berliners and East Germans began, as the West Berliners put it, "voting with their feet." During the 30-month period from November 1958 through July 1961 West Berlin became the escape hatch for a steadily increasing stream of East German refugees. In July 1961 as many as 3,000 escaped in a single day. The daily average for July and early August was about 1,800 per day. In terms of manpower, East Germany was bleeding to death. The Communist leadership solved the problem with brutal simplicity. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. THE BERLIN WALL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.

LAW AND POLICY During the Berlin Wall Crisis, the basic principle of American policy remained unchanged: International agreements have the force of law and cannot be changed except by the common consent of the countries that made them. They cannot be changed by force or the threat of force, but only by negotiation. American history had shown that the American people wanted to live in a law-abiding world, which would be possible only if all countries lived up to their international commitments. The principle was simple. The United States, Great Britain and France were (and are) in Berlin as a result of international agreements made with the Soviet Union. Those agreements apply not just to West Berlin, but to Greater Berlin as defined by law, all of it. As a result, throughout the Berlin Wall crisis, the United States refused to compromise on agreed rights deriving from the four-power status of the city. Men of the Berlin Brigade went on patrols along the Wall and to East Berlin because free circulation to all parts of the city was the right of the United States under international law. Rather than sacrifice even the tiny exclave village of Steinstuecken, General Clay flew into it by helicopter in September 1961. Thereafter, until October 1972 (when the problem was solved by agreement), a three-man detachment of Military Police from the Brigade's 287th MP Company was stationed there and rotated by helicopter. Their presence was not just symbolic; it was necessary since the East Germans harassed the residents crossing the access roadway through East German territory, frequently refused ambulances and fire trucks and prevented West Berlin police from entering the village by road. As General Clay saw it Steinstuecken was by law -- and today remains -part of the American Sector. 12. THE AMERICANS ARE STILL HERE Taken together, the events of the Berlin Wall Crisis were the most serious in the city's post-war history. Confrontations with the Russians at the autobahn and rail checkpoints and in East Berlin during the years between 1958 and 1965 were frequent; detentions were sometimes prolonged. Whether it was Soviet APC's trying to enter West Berlin, or Soviet jet fighters constantly buzzing the city, intentionally creating sonic booms, the Berlin Brigade showed the flag, reassuring the people of West Berlin that they would not be forced to live under East German rule. What that meant in human terms was illustrated by an incident which occurred at the height of the Wall Crisis. An American reporter asked a calm Berliner if he wasn't worried that the Allies might be forced out of the city. By that time, crisis was almost "normal" for Berlin. The Berliner shrugged. Yes, he was worried. But..."Your families are still here." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. EASING TENSIONS - THE ERA OF NEGOTIATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. VIETNAM ERA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. BRIGADE OF THE SEVENTIES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most significant

and far-reaching of the events shaping the Army of the seventies was

the decision to create an all-volunteer Army. Historically related

to that decision were new training concepts which, taken collectively,

constituted the broadest, most imaginative and ambitious program in

the Army's 200-year history. In 1972, the Army announced the concept of "decentralized" training, which fixed the initiative for planning and executing unit training at the company level. To provide additional variety and scope for initiative the idea of "adventure training" came into play the same year. Adventure training was not a substitute for standard training requirements. Berlin Brigade units continued to train in company class rooms and areas, sports facilities and in the wooded areas of the city. They also participated in Allied field training with the British and the French. Army training tests, tank and artillery qualifications were conducted at USAREUR's Major Training Areas in West Germany. Adventure training, however, was an opportunity that rewarded leadership initiatives, fostering esprit, the "All the Way" spirit. In this area, the "firsts" of the Berlin Brigade showed the Army in Europe what could be accomplished. During 1973-74 Berlin Brigade achievements in adventure training included mountain training in Italy, France and Scotland; skiing in southern Germany; crossing the English Channel in kyacks; and scaling the heights behind the Normandy beaches, reenacting the World War II landing on the coast of France (6 Jun 44). Brigade units also scored firsts in combining normal training activities with normal mission activities. Showing the flag, of course, remained a vital part of the mission. Rarely has it been shown more dramatically than in January 1975 when the 4th Battalion, 6th Infantry, accompanied by the USCOB, the Brigade Commander and members of the General Staff, conducted the first marathon Wall run" along the entire 100-mile circumference of West Berlin. Berlin's urban environment is such that, in mission training, high priority is given to combat in cities. To facilitate this type of training, a new combat in cities range, with concrete structures closely simulating actual conditions was completed in the spring of 1975. In addition, several times each year units of the Brigade use the West German Army's training village at Hammelburg near Schweinfurt. Finally, since 1972 the Brigade Staff has periodically reviewed both training experience and recent historical models as potentially significant for Army-wide, combat in cities doctrine. Now as in the past t is an exciting time and a rewarding experience to serve with the Berlin Brigade. 16. THEN AND NOW Deeply imbedded in the traditions of the Berlin Brigade are the harsh realities of the environment in which it serves. Running through what once were store fronts, through woods and along waterways, the Wall itself is an inescapable reminder of the Brigade's mission. It is not along the Wall, however, but along the city's great boulevards, especially the Kurfuerstendamm, that the reason for the mission becomes clear: Two million people, undaunted by the Wall, daily express their belief in freedom, progress and human dignity. In May 1975, speaking before Berlin's House of Representatives, the Secretary of State recalled these basic American values, of which free Berlin had become a living symbol, adding: "This is why this city means so much to us. For thirty years you have symbolized our challenges; for thirty years also you have recalled us to our duty. You have been an inspiration to all free men." The pride and tradition of the Berlin Brigade are inseparable from the challenges of service in a unique situation. Nor is "unique" an exaggeration. The situation of West Berlin since World War II has no close parallel in human history. From uniqueness has evolved a unique and complex set of problems. A careless action can create an international incident; a hasty or ill-considered action can create a precedent which opens the door to still other, unforeseen difficulties. The facts of geography are adverse and Berlin remains vulnerable to every wind of change. Confronted at every point of the compass, it is the enduring distinction of the Berlin Brigade to live with the dangers and rise to the challenges. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

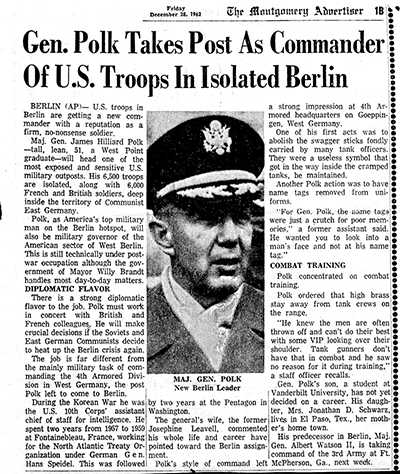

| 1962 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: The Montgomery Advertiser, Dec 28, 1962 (Montgomery, Ala.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1963 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: STARS & STRIPES, Aug 11, 1963) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Berlin Brigade Conversion under ROAD The Brigade will retain the engineer company (42nd Engr Combat Co), the support troops and the Berlin hospital under ROAD.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Berlin Brigade Maps | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1950 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: Guide to Berlin Militart Post, 1950) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

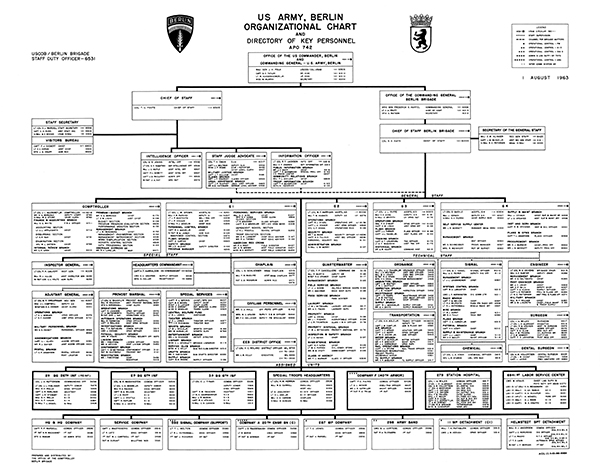

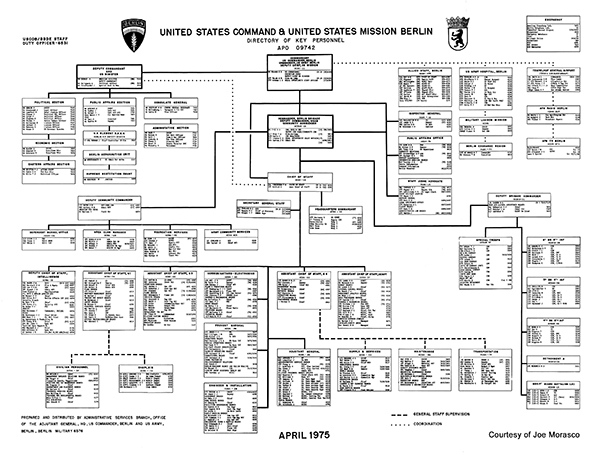

| Berlin Brigade Organization Charts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1963 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1975 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: American Forces in Berlin - Cold War Outpost, by Robert P. Grathwol and Donita M. Moorhus, DoD Legacy Resource Management Program, 1994) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Berlin Sentinel - Some of the issues published while in Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISSUES IN COLLECTION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aviation Detachment, Berlin Bde | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In the early 1950s, the 6th Inf Regt was using Hiller H-23 heliopters to patrol the western sector of Berlin. The regiment's air section was stationed at Tempelhof Airfield. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1956 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: Army Aviation Magazine, Dec 15, 1956) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iron Curtain By YC, (Capt.) Sylvester J. Hunter BERLIN, GERMANY -- Thought the readers of ARMY AVIATION would be interested in knowing a little about what goes on in the only Army Aviation Section located 110 miles behind the Iron Curtain. For record-keeping purposes, we are the Section of the 6th Inf Regt, probably the only Regiment having 3 H-13 copters assigned to it, and rarer still, only two authorized pilots. I italicize the word, "probably," for I've seen what happens to those who make bold-faced statements in "AA" about being the only units to do this or that. They're engulfed the next month by those who take exception. Our local flying area consists of the three west sectors of Berlin or approximately 185 square miles. We are limited to this area by our own Hqs but legally we could fly in a 20-mile radius of the center of Berlin. Needless to say, we do not mind the limitation. As for missions and operations, they are quite normal in most respects but sometimes turn out to be very interesting and amusing. For example, we held a training problem with the Regt in the Grunewald Forest (which actually is a large park). It was rather difficult for anyone to maintain the proper concentration and enthusiasm for the problem when you have a huge nudist colony right smack in the middle of the attack zone. Periodically, the question of an L-23 is brought up. Although we certainly can use an L-23 to maintain proper liaison with the various headquarters in West Germany, the question always hits a snag someplace. We have a real need for this craft and I hope that someday certain people in the Army will realize that we are no longer Cub pilots. With only choppers authorized, you may wonder how we meet our instrument minimums. We get most of our annual instrument flying with the AF in C-47s. In addition to supporting the Regt, we also serve the Berlin Command and USCOB with Army aviation support. Assigned AAs are Lt. Clardie A. White (Maint, Supply, & you name it) and yours truly as Chief Honcho. Also logging time with us is Maj. Donn T. Boyd, asgd to the Regt with duty in MOS 1542 (Exec, 3rd Bn). Six chopper mechanics, a clerk, and a driver complete the Berlin crew. I'd like to issue an invitation through "AA" to all Aviators who desire to and can manage to visit this divided city to come up and see us any time. We guarantee to roll out the carpet (not Red) and give you your choice of the $25 or $50 tour. For those arriving between May & October we have a Super-Duper $100 Tour which includes, among other things, the four points on our situation map labeled "NC." This is a new symbol I've learned since I taught the "Aviation Section Situation Map" in the AAS several years ago. Auf Wiedersehen from the only remaining WW II occupied area. (Ed. An explanation of the new map symbol can be found in the third paragraph.) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1968 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: STARS & STRIPES, June 11, 1968) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Army Aviation Detachment, Berlin Brigade The Army Avn Det, commanded by Col William S. Cox, has a complement of The Detachment is located at Tempelhof Air Base (an Air Force installation). Its hangars are close to the commercial side of the airfield. One of the missions of the detachment is to run helicopter patrols (aerial surveillance) along the Berlin Wall and rest of the border surrounding West Berlin -- to supplement other (jeep and boat) border reconnaissance missions performed on the ground by other elements of Berlin Brigade. These border patrol flights have been going on since the late 1940s. The short flight (US Sector only) is run daily - once or twice a week the Det runs a long flight that encompasses the British and French sectors. A regular patrol crew consists of pilot, copilot, crew chief and a Brigade G-2 observer (who is picked up at Andrews Barracks). Other missions of the Det include brigade troop lifts in support of field exercises and border orientation flights for visitors, including British and French officials. (British and French forces in Berlin do not maintain helicopters in their sectors.) Routinely, one helicopter is used to fly in supplies to Army MP's who are assigned guard duty in the Steinstuecken Enclave. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: Email from Aydin Mehmet, Germany) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: BERLIN OBSERVER, Aug 4, 1989) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aviation Det. holds flight safety record By Ron Gardiner |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The detachment's maintenance facilities include two overhead hoists, and the mechanics and technical inspectors do all authorized work under the light's green glow in the football-field-size hanger on Templehof Central Airport's flightline. According to Safety Officer CWO4 Eddy King, the award is for day-to-day safety, working every mission as safely as possible, not only the pilots, but the maintenance team and operations office as well. The unit was able to maintain a zero accident record by pulling together as a team, he said. The unit's personnel perform many checks to keep the aircraft safely in the air, and determine the ones in need of repair. According to Maintenance Officer Capt. Thomas Gainey, they use the phase inspection system to thoroughly check out each aircraft every 150 flight hours in a six-phase series. Some of the checks include taking oil samples and changing the interior transmission filter. Others require the engine be flushed. The safety record goes back well beyond the award dates. The last major aircraft accident was in 1969 when a helicopter made an emergency landing in a Mariendorf garden. Since then only one minor incident has been reported; a bent propeller on one of the observation planes in 1982. In addition to the unit's safety record, it has a record of hospitality. From 1961-72 the unit flew a "mini-airlift" to the exclave of Steinstucken providing those isolated residents of Zehlendorf supplies and greater access to West Berlin. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: BERLIN OBSERVER, Nov 30, 1990) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aviators fly 21 years accident free The Berlin Brigade's Aviation Detachment completed another year of accident-free aviation duty Sept. 29. With nine aircraft in the detachment's inventory, the unit logged more than 1,500 hours. The event commemorates 21 years of safe flying within Berlin air space. The unit's mission includes VIP flights, air assault, static displays, and formation flying. Aviation safety officer CW3 Frank Cicneros said, "Safety starts when we wake up in the morning and continues through the entire day, until we go to sleep. Safety is our job. If we don't do things right the first time, accidents happen and people get hurt. The combined effort has paid off. Safety is not taken for granted. Our goal has been to train safely." Lieutenant Col. Doug Powell, Aviation Detachment commander, has a philosophy of system safety and ensures its principles are used within each section of the organization, Cicneros said. The Operation Section is responsible for planning, scheduling and executing all missions in a timely manner. Two essential ingredients are assigning crews based on their experience level, and ensuring that all crews have been properly briefed before take off. Also, Operations mandates that each pilot in command gives pre-flight briefings to ensures the missions are fully understood. After each flight, the pilot in command is required to give a post-mission debrief to Operations detailing the mission, Cicneros said. The Standardization Section ensures all crew members are current and qualified in their aircraft. Their rigorous standardization program consists of no-notice check rides, annual flight evaluations and written examinations, he said. The Maintenance Section ensures that sound maintenance practices are applied before flights. This prevents in-flight maintenance-related mishaps. A system application of safety management principles includes daily inspection of each aircraft before and after every flight of the day, regular intervalinspectionsevery 25,50 and 150 hours, technical inspections of all work, and test flights to confirm flight readiness, Cicneros said. Also, the unit's Quality Control Section works with mechanics to ensure by-the-book procedures. With 12 soldiers, nine civilians and a secretary, the maintenance team is responsible for the tool room, battery, calibration, aviation life support, avionics, and prop and rotor shops. In his role as aviation safety officer, Cicneros advises, recommends and makes on-the-spot corrections to ensure that all workers get proper safety information, he said. The safety officer advises the commander with sufficient input to maximize mission readiness. tie implements a program to reduce accidental loss of material and injury to soldiers. But his primary responsibility is to be a fully operational pilot whose focus is on safety. In addition to conducting monthly safety meetings and inspections, he ensures that aviation operational procedures are developed to maximize safety and mission accomplishment. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signal Support Company, Berlin Bde | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: ECHO, March 1987) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Bocksberg - Berlin link, covering a distance of over 100 miles, will be the first digital troposcatter link that the Army has installed. With the Berlin link, FM stereo transmissions and reception will be provided to Berlin. Also, Helmstedt and Drachenberg (comm site west of Helmstedt) in the FRG will be able to receive AFN TV broadcasts. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: Email from Steve Burgess, Bocksberg DCS, 1989-93) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I spent over three years on this site and closed it in the fall of 1993. We maintained the digital communication link between DSC stations and a direct tropospheric scatter link between ourselves and BBG was transferred to the Signal Support Company, HQ, Berlin Brigade. This transfer took place sometime in 1987/1988, prior to my arrival. During my stay, we were attached to Helmstedt (1989-1991), which fell under the command of the Berlin Brigade during the same period. The opening of the east led to the closure of the site and the command of the site was transferred to the Helmstedt detachment and then on to the Berlin Brigade before final closure. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 298th Army Band | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

298th Army Band DUI

298th Army Band DUI |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

298th Army Band Blazer Pocket Patch 298th Army Band Blazer Pocket Patch |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7773 Signal Service Company | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: Email from Ed Gibson, 7773 Sig Co, 1951-1953) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| When I arrived in Germany in late 1951, I went to the replacement depot at Sonthofen, where I was told I was going to radio operators school at the Ansbach Signal School. Following that, I was assigned to the 7773 Signal Co in Berlin. It's name was changed later but I can't remember the new one. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| After crossing

the Russian zone, the radio cars were dropped off at

Helmstedt, and made the return

trip on the Eastbound trains. There were 6 operators on duty, two

on each train, one at Helmstedt, and one at the Clay HQ compound in

Berlin. Three operators were stationed at Helmstedt on a rotating

basis. I spent 9 months there in 1953. There were only about 20 Americans

stationed in Helmstedt, mostly MPs manning the checkpoint out on the

Autobahn. We were living in the biggest mansion in town. In addition to train duty, the 7773 also drove an SCR-399 in the weekly convoy which went from Berlin to Braunschweig and returned the following day. I still remember the call signs: The operating frequency was 5295 kHz. If you are familiar with the Morse code, imagine sending a name like Niederdodeleben with a Morse key from a swaying railway car. Great fun. But that was 50 years ago. Hope this fills you in a bit. The 7773 was involved in many other aspects of communications around Berlin, but I am not familiar with the details. I do know that radio-equipped vehicles were always on standby for use by high-ranking command officers during alerts. Ed Gibson |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VARIOUS ADDITIONAL DUIs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VARIOUS ADDITIONAL PATCHES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related

Links (Links verified 2/25/2025; inactive links removed): U.S. Army Berlin Brigade - website established by a former Berlin Brigade DEH employee. Nicely organized. Berlin - 1969 - a well researched and very interesting website hosted by Robert W. Rynerson who serve as a Russian-English Interpreter in the Rail Transportation Office in Berlin. Great "duty train" stories and information. Berlin Brigade - website dedicated to the veterans of the Berlin Brigade. Berlin US Military Veterans Association - A veterans association established for the benefit of all Berlin US Military Veterans and Active Duty Members who served in Berlin from 1945 to 1994. Getty Images - McNair Kaserne photos page. This is a commercial website that clients use to search and browse for images, purchase usage rights, and download images. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

mod 600.jpg)